Lessons for the Recovery: Wisdom from Angela Blanchard on Asheville’s Path Forward

In the weeks since Hurricane Helene tore through Western North Carolina, the landscape—and its people—are still finding their footing. Twisted remnants of homes scatter the hills and valleys; the floodwaters have long receded, but their impact lingers.

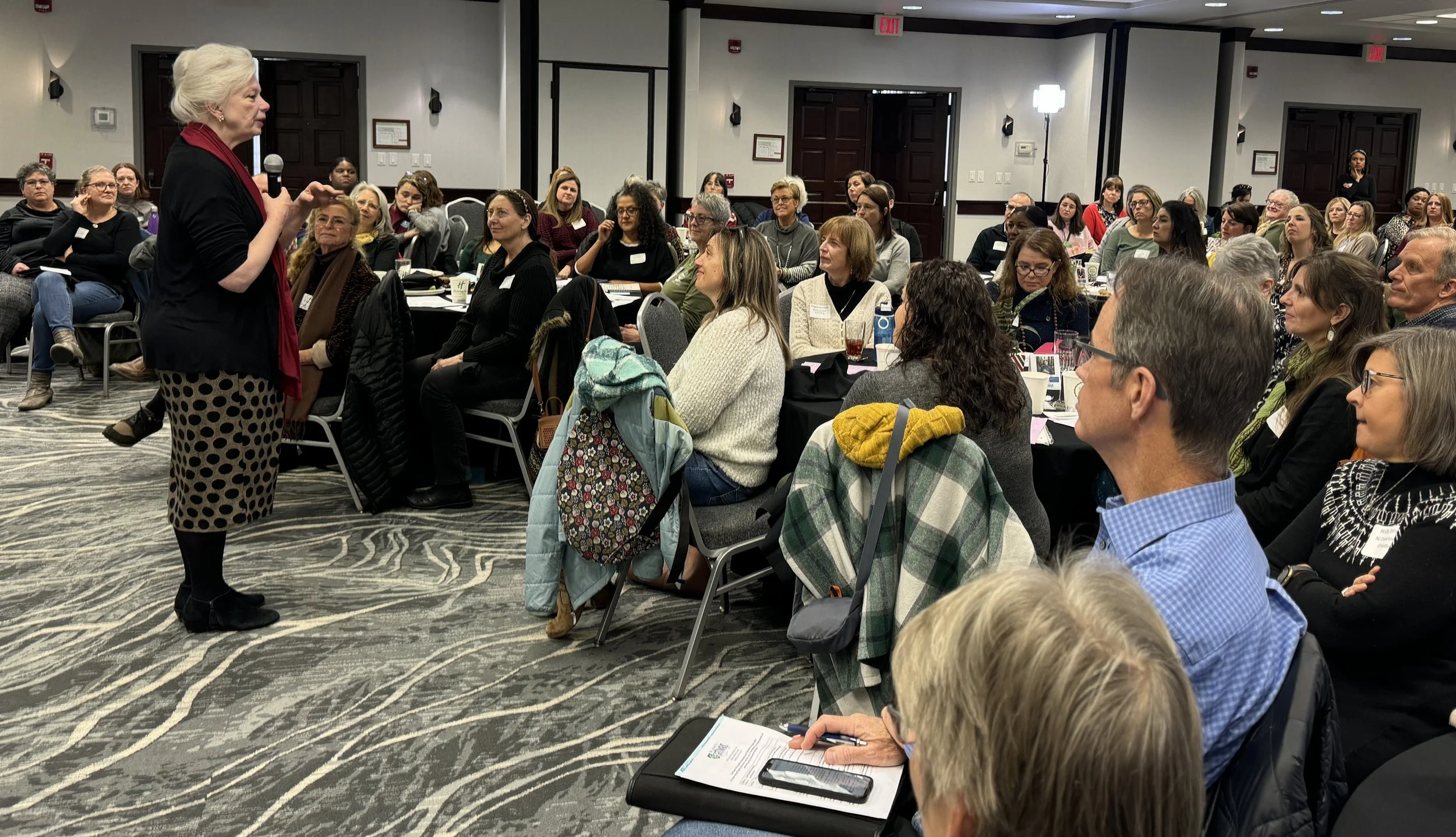

To rebuild, though, is not simply a matter of brick and mortar. It is a reckoning with loss and a conversation with hope. This was the message Angela Blanchard carried to the region when she visited in early December, invited by Thrive Asheville as part of our “Lessons for the Recovery” series. Her words were not comforting platitudes, nor was her presence merely symbolic. She came with the hard-won wisdom of someone who has weathered the worst—Hurricanes Katrina, Harvey, Ike—and walked communities through the slow, uneven process of becoming whole again.

“We are all vulnerable creatures sharing a common journey,” she told those gathered, her voice calm but unflinching.

Blanchard, now Chief Resilience and Recovery Officer for the City of Houston, has spent decades where few dare linger: in the liminal spaces where disaster meets recovery, where communities must decide how to rise and whether to simply rebuild—or to become something new. In Asheville, she met with local leaders, first responders, and residents who are all, in their own ways, still trying to make sense of Helene.

The Journey Through the Phases

Disaster, Blanchard explained, arrives in phases. First comes survival and sanctuary, an instinctive return to what is essential: safety, shelter, one another. “You didn’t have a plan for this storm,” she said, not with judgment but recognition. “This reflex we have to open our homes, to make sure people are welcome—we don’t need a playbook for that. We as a species know how to do it.”

But soon, survival gives way to chaos and collision—a phase familiar to anyone who has tried, and failed, to restore normalcy after their world has turned upside down. “What was once easy becomes hard; what was once hard becomes impossible,” Blanchard said. “We simply can’t accept that things don’t work the way they used to.” The frustration, she warned, can feel suffocating. It can fracture communities, turning allies into adversaries. “Try to avoid thinking, if only they would,” she urged. “It’s miserable.”

It is in this chaotic space that many people burn out, moving into a period Blanchard calls limbo—a silent, invisible phase where exhaustion masquerades as inaction. “When people hit limbo, it looks like they’re doing nothing,” she explained. “But what’s happening inside is that they’re orienting to a new reality.” In other words, what seems like stagnation is often the first fragile step toward something new.

Then comes the reckoning: the collective act of taking stock, of understanding that old systems—ones that failed some and served others—are too brittle for this new reality. “The perfect recreation of what you had is off the table,” Blanchard said. “But you are free to make it up. You have the opportunity to craft something new—something better, perhaps—using what you have, where you are, right now.”

Gratitude and Grief, Side by Side

For Asheville, Blanchard’s presence was a gift of clarity: a map for the long road ahead and permission to grieve what was. “This place will always have a before and an after,” she said. “The moment you cross that bridge from before Helene to after Helene, that’s now a part of your story. The disaster chose you, and you are the equal of it.”

She urged the community to hold rituals for what was lost. “Gratitude and grief will live side by side for a long time,” she said. “Allow that. It belongs together.”

Her practical advice was just as resolute. Rebuilding cannot happen in silos: public, private, and philanthropic sectors must align. No one, she insisted, must be invisible. “Rage and despair are the reactions of those who are written off,” she warned.

And yet, she spoke of hope. Of possibilities unearthed by disaster. “How do we take this opportunity to create anew? What would this be like if it worked for everyone?”

The Willing and the Worthy

Blanchard left Asheville with a final charge to its leaders and residents: “Build a coalition of the willing. Grant grace to those who can’t join you yet, and leave the table open for when they’re ready. Every grievance, every complaint holds within it a vision of a hoped-for future. Listen to that vision.”

And, perhaps most importantly, she offered a promise—earned not through empty optimism but through lived experience. “When you’ve been to hell and back together, there’s a fundamental trust that grows. You’ll trust yourselves in a whole new way. You will know that whatever happens next, you’ve met it before—and you can meet it again.”

For Asheville, as for every place scarred by disaster, the road forward is uncertain. But Blanchard’s visit has given the community something far more valuable than answers: a belief that they are equal to the task, and that the trust, strength, and wisdom forged in hardship will sustain them far beyond recovery.